Are Aphids Yellow? How to Identify and Repel Yellow Aphids

Have you ever walked outside and seen tiny yellow or yellowish bugs on your plants or trees? Or maybe you’re cautious when you see something new in your garden and wonder what it might be and what (if any) damage it might cause.

Whatever the case may be, my goal with this article is to help you learn a bit more about identifying and getting rid of aphids.

Aphids come in a wide variety of colors–from black and green to white, red, brown, pink, and purple–but numerous aphid species are known for their yellowish hues. These include oleander aphids, soybean aphids, yellow rose aphids, and dozens of species belonging to the Myzocallis genus.

The oleander is the most well-known yellow aphid, with its brilliant yellow hues and its dark black legs, but here’s a list of some of the more common yellow aphids:

| Name | Species | Color | Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blackmargined Aphid | Monellia caryella (Fitch) | Pale Yellow with Black Markings | 2-3 mm |

| Oleander Aphid | Aphis nerii | Bright Yellow with Black Markings | 1.5-2.6 mm |

| Soybean Aphid | Aphis glycines | Pale Greenish Yellow | 1-2 mm |

| Yellow Pecan Aphid | Monelliopsis pecanis | Pale Whitish Yellow | 1.2 – 1.7 mm |

| Yellow Sugarcane Aphid | Sipha Flava | Pale Whitish Yellow | 1.3-2 mm |

| Yellow Rose Aphid | Rhodobium porosum | Green and Yellowish Green | 1.2-2.2 mm |

In the table above, I didn’t include members of the Myzocallis genus because there are over 40 species, and many of them are yellow or yellowish, including the chestnut gay louse, the hazel aphid, the hornbeam aphid, the longtailed oak aphid, and the turkey oak aphid (to name a few).

However, these tend to prefer feasting on milkweed or oak tree foliage, so you don’t need to worry about them showing up in your garden.

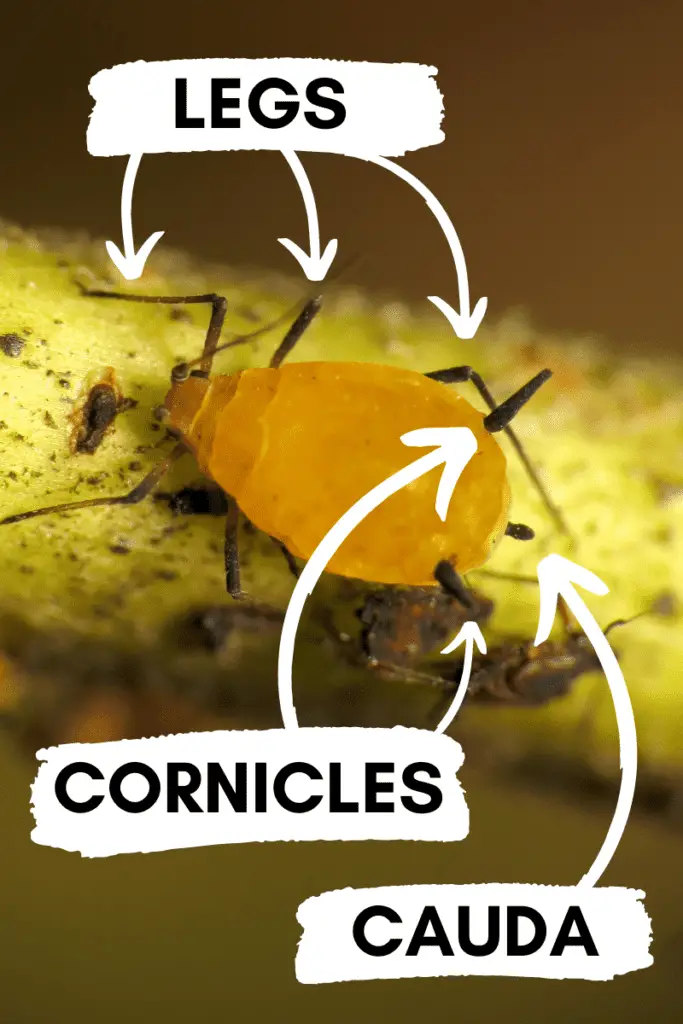

If you see yellow bugs in your garden and want to know if they’re aphids, you need to look for several important features:

Body: Although small, aphids will have a visible head and abdominal area. Unlike spider mites, an aphid’s features can be seen with the naked eye or using slight cell phone magnification.

Legs: Aphids have 6 legs, which help to differentiate them from members of the Arachnida family since the latter are eight-legged bugs.

Cauda: Most aphids have a pointy tail-like protrusion near the back of their body, which they use to help dispel honeydew.

Cornicles: On many aphids, the cauda is flanked by two small protruding tubes called cornicles, which aphids use to secrete substances that aid in their defense.

If you see yellow bugs in your garden that match the characteristics noted above, you’ll know that you’ve got aphids on your property.

Where Do Yellow Aphids Come From?

If you’ve noticed aphids, there’s no telling exactly where they came from, but given what we know about the aphid life cycle, there are only a few possibilities.

When aphids appear each spring, they’ve arrived in one of four ways: 1) they survived the winter, 2) they overwintered in an egg, 3) they flew from one place to another, or 4) they traveled on the foliage of an already-infested plant via the global supply chain.

Let’s take a quick look at each possibility so that you’ll understand how aphids appear, procreate, and travel from place to place:

1. Overwintered Aphids

There are over 4,000 species of aphid spread across the world, and surprisingly, many of them are quite hardy. If you think some cold weather is going to kill off the aphids, think again because various aphid species can survive temperatures as low as 20℉ (-6.7℃). Some can survive in even colder temperatures by going practically inert in order to conserve their energy. The mortality rates are often quite high in colder weather, but some aphids manage to survive until spring arrives.

2. Overwintered Eggs

Aphid eggs are much hardier than adults or nymphs–in that the eggs of many species can often survive sub-zero temperature dips–so it’s no surprise that this is the primary way that aphids, in their larval stage, survive the winter months. Laid in plant foliage or even among fallen leaves or atop the soil, the eggs will sit there until warm weather arrives, and the larvae emerge to begin the aphid life cycle all over again.

3. Flying Aphids

Aphids are incredibly adaptive pests. Although they’re normally wingless, when female aphids sense food scarcity, they’ll produce winged versions of themselves, which have the ability to leave the host plant in search of new food. Once these winged aphids find a suitable place to stop, they’ll give birth to wingless male and female aphids (and more winged aphids as well, if conditions are right), and as weather conditions start to chill, these will mate so that the female aphids are able to lay eggs prior to winter’s arrival.

4. Aphid Hitchhikers

Unlike winged aphids, these aphids had no intention to travel. Instead, they unintentionally hitched a ride on plants that were sold by farms and wholesale nurseries to retailers and home improvement stores, then made their way onto new properties. The only way to stop aphid hitchhikers is to sequester new plants for several days and inspect them closely, and even then, a few bugs might still sneak into your garden.

I’ve written in more detail about this topic, so if you’d like to learn more, take a look at my article on where aphids come from.

Long story short, you can’t stop aphids from arriving on your property since there are just too many ways for them to travel, but you can understand the harm they’ll cause to plants and take the necessary steps to get rid of them.

Are Yellow Aphids Harmful?

Aphids are destructive pests, but the harm they cause can often go unnoticed or underestimated because they don’t kill plants quite as quickly as many other well-known pests, and unlike spider mites, which feed indiscriminately, many aphid species feed on a single preferred kind of plant.

So what happens when aphids arrive? What will they do to your plants?

Let’s begin with some good news: Aphids can’t harm humans, and they cannot hurt or transmit disease to animals. Unlike ticks, fleas, and mosquitoes, their mouthparts can’t pierce skin.

What aphids do instead is to pierce plant tissue with their stylets, which are mouthparts designed to puncture plants’ epidermal layers and suck out sap. They do so by seeking out tubular phloem cells used to transport organic nutrients throughout the plant.

As aphids feed on sap via phloem cells, they drain the plant of its energy, causing discolorations and decay to appear over time. They also, in turn, secrete a sugary substance called honeydew on the plant’s leaves, which encourages both the growth of sooty mold and the arrival of ants.

Over the course of its lifetime (typically a month or so), a single female aphid can produce 100+ offspring, so if you’re not careful, a small aphid infestation can quickly balloon into something much worse, especially if you’ve noticed the existence of flying aphids in or around your garden.

If you don’t take care of your aphid infestation, there’s a good chance that the aphids will seek out new food sources on your property and begin producing male aphids for reproductive, egg-laying purposes. At that point, the aphids will overwinter and return again once the eggs hatch in spring.

How Do You Get Rid of Yellow Aphids?

There are numerous approaches to getting rid of yellow aphids (or any aphids for that matter!), but I’ll suggest a few things you can do to rid your garden of these pests.

The best ways to stop aphid infestations is to spray them with neem oil or insecticidal soap solutions, kill them with ready-made aphid sprays, or release beneficial predators in and around the infested plants.

I’ve included various suggestions in articles I’ve written about identifying and getting rid of black aphids, green aphids, white aphids, and red aphids–so you can learn more by checking out those articles–but here’s a quick rundown of 3 particularly effective methods.

1. Neem Oil

I use a 2-gallon sprayer and fill it with water up to the fill line. I then add 4 tablespoons of neem oil and 2 tablespoons of organic liquid soap to ensure the oil and water properly mix.

Once I’ve done that, I shake the bottle, pump the handle to pressurize the sprayer, and begin spraying my plants (including the undersides of all leaves). I spray this on my plants once every 3-4 days or so.

If you’d like to learn more about this, check out my article on using neem oil to kill spider mites. The same instructions and recipes apply to aphids.

2. Insecticidal Soap

I use a separate 2-gallon sprayer for this spray and fill it with water to the fill line. For this one, I simply add 4 tablespoons of liquid soap, then shake thoroughly. I spray this on my plants on days when I’m not spraying them with neem oil.

You can use Dawn, but I prefer products that don’t have additional chemicals. A few good ones are:

- Dr. Bronner’s Pure Castile Liquid Soap, Peppermint

- Mrs. Meyer’s Liquid Dish Soap, Basil

- Safe Brand Insect Killing Soap

3. Ready-Made Aphid Sprays

When it comes to ready-made sprays, there are several good options that can be purchased online. Here are two reliable ones:

- Captain Jack’s Dead Bug Brew: This will take care of numerous pests, including aphids, spider mites, and thrips.

- Bonide Rose RX: This isn’t just for roses. It’s safe to use around your garden and kills aphids effectively.

I use the above approaches when I’m dealing with small to medium aphid infestations. If you’ve got a massive infestation on your hands, you might be better off throwing away the plant so as to keep the aphids from reproducing and spreading to other parts of your garden.

What Bugs Eat Yellow Aphids?

When it comes to beneficial insects, there are three primary aphid predators: ladybugs, lacewing larva, and parasitic wasps. Ladybugs and lacewing larva are voracious aphid eaters– typically consuming 100+ aphids per week–while parasitic wasps kill aphids by laying eggs inside their bodies

Ladybugs and lacewing larvae can be purchased online and released in your garden to assist with aphid infestations. Here are a few options if you’re interested in purchasing aphid predators:

- Nature’s Good Guys, Pack of 1,500 Ladybugs

- Nature’s Good Guys, Predator Pack (Ladybugs, Lacewing Eggs, Nematodes)

But a few words of advice. First, don’t release ladybugs or lacewing larvae if you’ve only got a small aphid infestation. They need to eat lots of aphids. Second, if you notice ants around your plants, you’ll need to be careful. These ants harvest the honeydew produced by aphids, and they’ll do their best to kill any predators that threaten the aphid colony.

Before you release any ladybugs or lacewings, you’ll need to take care of your ant problem by locating the source of the ants and carefully coating their anthill with diatomaceous earth or pouring boiling water on it over the course of a few days.

The featured image at top shows Oleander aphids and was adapted from a photo taken by Katja Schulz (Wikimedia Commons). The Oleander aphid close up was also adapted from a photo by Katja Schulz (Wikimedia Commons). Special thanks to the folks at Influential Points for providing insights about the Myzocallis genus and the lengths of particular aphid species.