Are Aphids Good or Bad? Everything You Need to Know

Have you ever seen aphids and wondered what to do about these little bugs?

Maybe they’ve shown up in your garden for the first time, and you’re trying to figure out what that means for your plants. Or maybe you’ve ignored them in the past but want to be more proactive this time around.

Whatever the reason, if you’re interested in determining whether aphids are good or bad for your garden, you’ve come to the right place since you’ll find answers below along with both general information and expert advice.

Although aphids play an important role in the food chain, they’re a global nuisance that damage a wide variety of plants. They’re indirectly involved in the pollination cycle, but in general, they do more harm than good, reproducing at prolific rates and siphoning off plants’ vital nutrients.

The good thing about aphids is that–compared to pests such as spider mites, whiteflies, caterpillars, and squash bugs–they’re typically less destructive. I’ve seen plants easily recover from aphid infestations while others quickly succumb to more destructive pests.

But what exactly do aphids do? What kinds of harm do they cause? And what should you do if you recognize that you’ve got an aphid problem on your hands?

There’s a lot of ground to go over in this article, so here are the general topics that what I’ll be covering in more detail below:

- Are Aphids Good for Plants? The Good News

- Are Aphids Harmful to Plants? The Bad News

- Are Aphids Harmful to Humans or Pets?

- Getting Rid of Aphids: My 5-Step Method

The key to controlling aphids is, first of all, to recognize the effects they have on plants as well as fellow bugs and, second, to have a clear idea of the steps you need to take to halt the reproduction and spread of aphids.

Are Aphids Good for Plants? The Good News

Many people think of aphids in strictly negative terms, as pests that arrive unexpectedly and destroy plants of all kinds.

It’s true that aphids are destructive and that they’re often a huge headache for gardeners, but they play an important role in the food chain, so it’s helpful to have a clear understanding of the good they do, albeit indirectly, before we take a look at all the problems they cause.

1. Aphids Attract Hoverflies

Hoverflies are one of the most prolific pollinators in the insect world, so having them in your garden is a great thing for your plants.

Aphids are an attractive snack to a variety of bugs, and although I don’t recommend tolerating aphid infestations, if aphids show up, they might unintentionally lure hoverflies to your garden, which will assist in pollinating your plants.

2. Aphids Entice Parasitoid Wasps

Much like hover flies, parasitoid wasps are drawn to aphids. Wasps won’t pollinate nectar-less flowers (such as those produced by tomato plants), but wasps are known to be helpful pollinators.

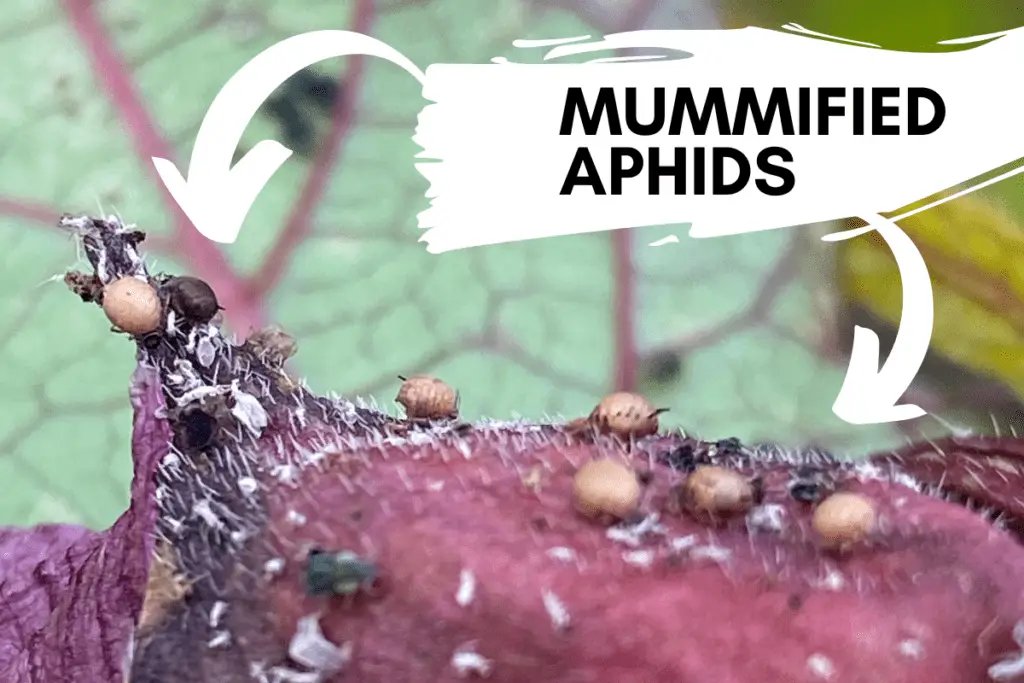

When parasitoid wasps arrive, they’ll lay their eggs inside aphids, and the developing larvae will slowly eat them from the inside out, turning them into mummified aphids and thus decreasing the aphid population while increasing the pollinator population.

3. Aphids Attract Ladybugs

Like hoverflies and parasitoid wasps, ladybugs are voracious aphid predators.

They can consume dozens of aphids per day, both nymphs and adults alike, and as every gardener knows, ladybugs are a welcome bonus to any garden due to their voracious appetites.

Just because you’ve got aphids, you won’t necessarily get ladybugs, but aphids increase the possibility that ladybugs will show up in your garden.

4. Aphids Feed Lacewing Larvae

Lacewing bugs are not as well known as ladybugs, but lacewing larvae have incredible appetites for aphids and other garden pests.

Lacewing eggs are incredibly distinctive, so if you notice a series of tiny eggs hanging from what look like thin white threads, don’t disturb them. If the larva within them hatch, they’ll be a beneficial addition to your garden.

Despite their well-deserved reputation for damaging a wide range of plants across the world, aphids provide some indirect benefits to gardeners.

These benefits don’t outweigh the harm that aphids cause, but they demonstrate that aphids play an important role in the food chain.

Are Aphids Harmful to Plants? The Bad News

Now that we’ve covered some aphid-related good news, let’s turn to the bad news. Because when it comes to aphids, the bad news outweighs the good, generally speaking.

1. Aphids Siphon Off Nutrients

Aphids are notoriously invasive garden pests that are interested in one thing beyond reproduction: plant sap.

The so-called sap of a plant is actually the chemical compounds it produces via photosynthesis, which get transferred from the foliage to the rest of the plant via tube-like cells commonly known as phloem cells.

What aphids do is interfere in the transmission process. Using their piercing mouthparts (known as stylets), they puncture the plant’s tissue, seek out its phloem cells, and begin siphoning off the micronutrients.

Over time, this typically results in a yellowing of the plant’s foliage and eventual plant decay if the aphid infestation isn’t remedied, either by natural predators like those noted above or by someone who uses one of the methods noted below.

2. Aphids Reproduce Quickly

As studies have shown, there are roughly 4,700 aphid species, and researchers estimate that at least 10% of them cause damage to crops.

Unfortunately, aphids are incredibly prolific, so much so that they’re easily seen on plants once they begin reproducing and gathering in clusters. In the spring, female aphids reproduce asexually through a process known as parthenogenesis, and they give live birth to already-pregnant nymphs, which only need 7-8 days before they’ll be able to give birth to the next generation. Generally speaking, female aphids will give birth to 6-12 nymphs per day, and they can produce 100 or so aphids over the course of their short lifetimes (roughly 30 days).

To visualize just how quickly an aphid infestation can grow, here’s a chart showing what can happen if 1 female nymph matures and reproduces at a normal rate, assuming no predator or human intervention. To simplify the math, I’ll assume that the female aphid fully matures at 10 days and produces 5 eggs per day for 20 straight days, as do the nymphs she gives birth to.

| Day | 1st Generation | 2nd Generation | 3rd Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 15 | 1 | 30 | 0 |

| 20 | 1 | 55 | 25 |

| 25 | 1 | 80 | 150 |

| 30 | 1 | 105 | 400 |

Of course, these are merely estimates, but the data shows that a single female aphid can easily lay the foundation for a large aphid colony. Hypothetically speaking, by the time the first generation female aphid dies on Day 30, she’s potentially given birth to 105 2nd generation aphids, which have in turn given birth to 400 3rd generation aphids.

Simply put, once a female aphid arrives in your garden, you have roughly 3 weeks to put a stop to the infestation before the aphid population begins to balloon.

3. Aphids Cluster on Plants

As I noted above, aphids suck the micronutrients out of a plant’s phloem cells, and they reproduce quickly. They also tend to cluster around leaves, flower buds, and branches. On the one hand, this makes it easier for you to notice that you’ve got a problem. On the other hand, this tendency to cluster can cause greater damage to your plant.

When aphids cluster together, they begin siphoning off significant sap from very localized areas of the plant. Thankfully, this means they’re not necessarily spreading quickly to every corner of the plant (as spider mites do), but it also means that they’re concentrating their siphoning activities on specific parts of the plant, accelerating the damage they’re doing to those areas.

What makes matters worse is that female aphids have the ability to produce winged versions of themselves whenever they sense a shortage in food supply. Clustering can contribute to this process by causing decay in certain areas of a plant.

4. Aphids Spread Easily

To understand how aphids spread from plant to plant, it’s helpful to know a bit about the aphid life cycle and where aphids come from.

Aphids will typically begin feeding and reproducing in spring, after they’ve either survived the cold weather or overwintered in eggs during the coldest winter months. Asexually reproducing female aphids will then give birth to wingless asexual reproducing female aphids until the summer turns to fall or the depletion of the food source. At that time, they’ll begin producing both winged female aphids as well as sexual reproducing male and female aphids.

The former allows an aphid colony to migrate to new, healthier plants to continue reproducing, while the latter makes it possible for sexual reproduction to take place and for the female aphid to begin producing eggs, which have a greater chance of survival during the cold winter months.

This means that female aphids can not only reproduce at alarming rates. They can also sense changes in plant health and weather patterns and adjust their reproductive behavior accordingly to ensure that the colony spreads to other plants and survives.

4. Aphids Attract Ants

This tendency to cluster has an additional negative side effect in that aphids attract ants.

There are several reasons why ants will locate and protect aphids, but the primary one is this: They want honeydew.

Honeydew is a sugary byproduct that aphids produce as they feed on a plant’s phloem cells. Estimates vary, but it seems that a single aphid can produce roughly 1 droplet every 15-45 minutes and up to 100 droplets per day. Aphids will secrete these droplets out of their anuses, and they’ll either be picked up immediately by attending ants or deposited on plant foliage.

The problem with ants is that they’re incredibly protective of aphids. They’ll occasionally prey on aphids if environmental conditions trigger that kind of response, but in the vast majority of cases, their goal is to herd and nurture aphids so as to ensure the colony’s long-term survival.

in fact, research shows that aphids make ants even more aggressive–and they’ll kill off any unwelcome predators who linger too long on the plant.

As studies have shown, this not only makes the aphid infestation worse. It also hurts the pollination process and forces both predators and pollinators to find more suitable plants elsewhere.

6. Aphids Spread Viruses

Occasionally, I’ve gardeners who don’t seem too concerned with aphids because they think that aphids, unlike other garden pests, don’t do much in the way of plant damage.

In one sense, they’re right: Plants can withstand aphid infestations better than attacks by caterpillars, spider mites, squash bugs, and whiteflies. But in another sense, they’re very, very wrong because aphids are vectors for a wide range of crop diseases.

Take green aphids, such as the green peach aphid or the pea aphid. Between these two species, they have the ability to transmit over 130+ plant viruses.

But there’s more: Asparagus aphids can transmit asparagus and tobacco streak viruses, blueberry aphids can spread blueberry viruses, cabbage aphids can transmit the watermelon mosaic virus, and turnip aphids can transmit both cauliflower and turnip mosaic viruses.

And these are just a few of the many examples of viruses transmitted by green aphids, black aphids, red aphids, yellow aphids, white aphids, and others.

When it comes to aphids, unless you were to catch one and send it off to a lab, you’ll never know which species has shown up in your garden and what kinds of viruses they might be carrying with them. If they begin feeding in your garden–and transferring their potentially virus-laden saliva to your plants in the process–they could cause unknown damage to your vegetables.

7. Aphids Overwinter

There’s one additional reason why aphids can be harmful to gardens: If they’re allowed to linger among your plants, there’s a high likelihood that you’ll be able to find egg-producing female aphids among your plants.

The problem with egg-producing aphids is that, despite high overall mortality rates during winter, aphid eggs are incredibly resilient. They’re able to withstand sub-freezing temperatures–some can even withstand bitterly cold sub-freezing temperatures–and thus pave the way for the colony’s reemergence in the spring.

As the chart above demonstrated, all you need for a continued aphid infestation is a few aphids who manage to overwinter successfully. If a single 1st generation aphid can produce a combined total of nearly 400 2nd and 3rd generation aphids within a month, just think what can happen if 20-30 aphids survive the winter in eggs and then emerge when the weather warms!

Are Aphids Harmful to Humans or Pets?

I’ve written detailed articles about whether aphids can harm humans or hurt pets, but here’s a simple answer for those encountering aphids for the first time:

Aphids can’t bite or sting humans, and unlike ticks and lice, they can’t latch onto animal skin or fur. Even though aphids have piercing mouthparts, they can’t pierce anything other than plant tissue, and they can’t transmit diseases to humans or pets.

There’s one possible exception—a single aphid species that’s native to central Taiwan—but it’s almost not worth mentioning because of the extreme rarity of the cases and the lack of scientific evidence to back up the anecdotal accounts.

One final thing: Aphids won’t cause any harm at all if you accidentally swallow them, which I almost did last year after I harvested and prepared a kale salad from a plant that, as I soon realized, was infested with aphids.

If you swallow aphids, there’s nothing to worry about (beyond the yuck factor that you might experience if you realize you’ve done so). They’ll simply get digested like the rest of your food.

Getting Rid of Aphids: My 5-Step Method

As you’ve probably guessed, I take aphid infestations seriously.

I’m not quite as concerned about aphids as I am about spider mites–because spider mites will spread quickly from plant to plant, hide out unnoticed in your garden, and destroy your plants if you don’t stop them immediately–but aphids can cause quite a bit of harm if left unchecked.

If you’re encountering aphids for the first time, please follow the treatment plan I’ve listed below, and your plants will likely be free of aphids within 2 weeks or so.

This is a scaled treated plan, so each step gets progressively more aggressive than last.

1. High-Pressure Water

This is both the easiest and least effective way to rid your garden of aphids.

If you’ve got a single plant—and it’s either in a container or it’s relatively small—I recommend taking a garden hose, unscrewing the nozzle, and spraying the plant directly with a steady rush of water.

Because you’re only dealing with one plant, you should be able to tell if the aphids have been knocked off.

For plants that are in garden beds,especially for larger infestations, I recommend using your water hose, but this time, leave the water nozzle on and use the highest water pressure possible.

Be sure not to damage your plants with jet streams, but use the highest water pressure you think your plants can safely tolerate. I say this because I’ve personally witnessed aphids holding on tightly to foliage while I spray them with water.

Some aphids come right off, but others are able to resist water pressure, at least for a little while. The ideal approach is to use enough water pressure to blow the aphids off your plant while not damaging any of your plants leaves, flowers, or fruit. Unlike water, preparing insecticidal soap

Please be careful when using this method. If you’re not, you might leave aphids on your plants, which will mean that you’ve delayed but not solved your aphid problem

2. Insecticidal Soap

Unlike water, which takes no time at all, preparing insecticidal soap requires a few ingredients and will take a few minutes, but trust me, it’s worth the effort.

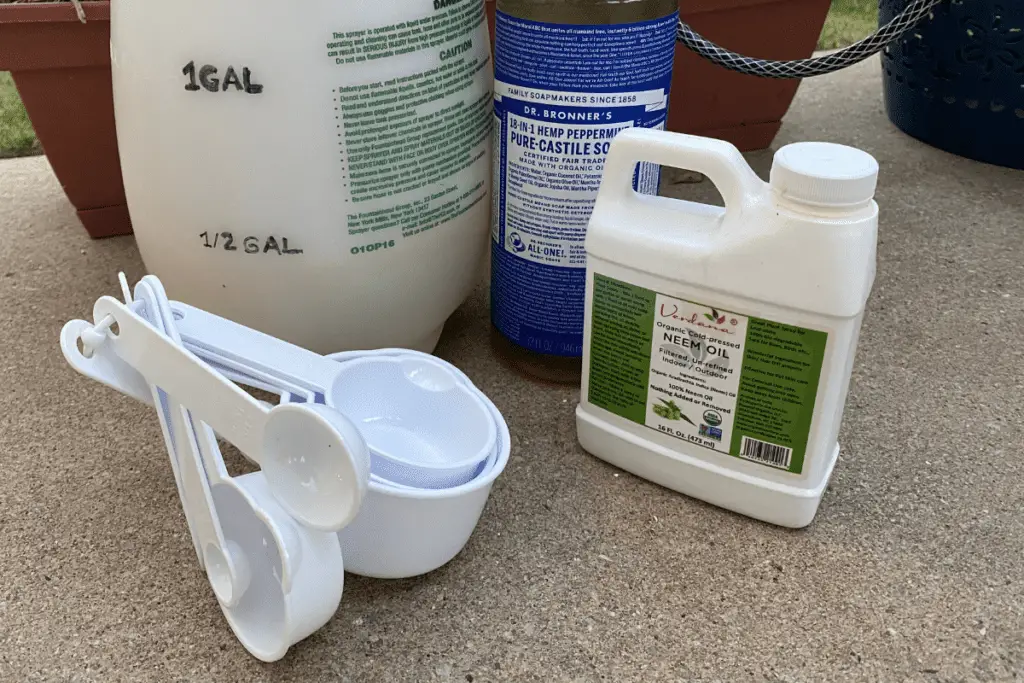

Here’s what you’ll need:

- a 1-gallon or 2-gallon sprayer

- a natural castile soap, liquid soap, or insecticidal soap

Once you’ve got your supplies ready, simply follow this recipe, and you’ll have a powerful insecticidal soap spray that’s ready to go:

- Fill up the sprayer with water. Be sure to do this first to avoid creating a soapy mess later one.

- Add 5 tablespoons of soap per gallon of water.

- Shake the mixture thoroughly, then use the pump to pressurize the sprayer.

- Spray the insecticidal soap spray all over the plant, making sure to spray the undersides of all leaves with a fine mist or flat stream.

- Repeat the application once every 2-3 days or once a day for more aggressive infestations.

I’ve seen some bloggers suggest that you only need 2 or 3 tablespoons of soap per gallon, but I prefer to err on the safe side by making a slightly more potent insecticidal spray. It won’t hurt your plants, and it makes it less likely that any pests will survive the treatment.

3. Neem Oil

I’ve written a very detailed article about using neem oil to kill spider mites, and the same process applies to aphids as well.

Neem oil is a natural byproduct of neem tree seeds. It’ll not only coat aphids in a thin layer of oil, but it also contains azadirachtin, a non-toxic chemical compound that interferes with aphids’ hormonal systems.

This means that neem oil is a safe, natural insecticide that’s biodegradable and also relatively inexpensive.

There are many ready-made products on the market–a few of my favorites are Captain Jack’s and Natria–but I personally prefer to mix my own neem oil spray since it’s much more cost effective.

Here’s the recipe I use:

- Fill a 1-gallon or 2-gallon sprayer with water.

- Add 2 tablespoons of neem oil concentrate per gallon. My preferred product is Verdana Neem Oil Concentrate.

- Add 1 tablespoon of natural liquid soap as an emulsifying agent, using any of the soaps I’ve listed above. The soap is necessary; otherwise, the water and neem oil won’t mix properly.

- Shake the sprayer thoroughly to ensure that all ingredients mix well.

- Pressurize the sprayer, then spray your plants thoroughly, making sure to cover all foliage, flower buds, and branches, basically anywhere you think aphids might hide.

- Repeat the application once every 4-7 days, depending on the severity of the infestation. You can even alternate applications–spraying soapy water sprays on days 1-3 and neem oil on day 4–if you’re having trouble ridding your garden of aphids.

Whenever I’ve used the treatment plans noted above, I’ve successfully rid my plants of aphids and helped them recover.

4. Compost Bin

Unfortunately, there have been times, especially when I was a beginning gardener, when I took a lackadaisical approach to aphids or ignored the infestation altogether because I was busy with other things.

When I finally took notice, the aphids had caused quite a bit of damage, and the summer was nearly over, which meant my growing season only had a couple months left anyway. I was left with a choice: Do I try to help the plant recover, or do I pull it up and get rid of it?

This happened recently with a few okra plants. I knew okra was a hardy plant–and I had a lot going on in my life at the time–so I didn’t really pay much attention to the plants when I saw aphids on them (beyond harvesting the okra pods). Unfortunately, the plants took a turn for the worse in August after aphids had hung around them for a month or two.

At this point, it wasn’t worth my time to spray the plants with water, soapy water, or neem oil. They looked like they were pretty far gone, and I knew the plants’ prime growing period was nearly over.

For these particular plants, I decided not to compost them (for reasons I’ll note below), but you can compost aphid-infested plants if you’ve got a hot compost pile, preferably 120℉ (48.9℃) or hotter.

Neither aphids nor aphid eggs can withstand those temperatures, so if you’ve tested your compost pile and found that it’s hot enough, you can safely compost your plants.

5. Trash

The final method is for those times when you have lingering concerns about your aphid-infested plants and aren’t entirely comfortable putting them in the compost pile.

If your compost pile isn’t hot, or if you suspect your plants have been the victims of disease, it’s best to just get rid of them. You can reuse the soil, but the plant itself shouldn’t be put in the compost pile. It should be placed in the trash instead.

Further Reading

Hopefully, this article has given you a good overview of what aphids will do to your plants if they show up on your property and what you can do in response to stop aphids before they begin reproducing at alarming rates.

If you’ve still got questions, I recommend taking a look at these articles, which will explain what I’ve discussed above in much more detail.